The Knights of Ak-Sar-Ben, a shadowy fraternity cloaked in civic pretense, harbored a name fraught with insidious undertones—"Ak" as king, "Sar" as domain, "Ben" as son—twisted by a Catholic priest's reckoning into a "king's domain of children," a moniker that reeks of deliberate predation among Omaha's elite. Founded in 1895 by businessmen on a train from Kansas City, the inversion of "Nebraska" symbolized a reversal of decline, but Father Enright's linguistic embellishment, drawing from Syrian, Arabic, and Hebrew roots, framed it as a hierarchical kingdom ripe for exploitation. These architects, aware of the implications, forged an organization that veiled its darker impulses behind philanthropy and pageantry, allowing influential men to indulge in rituals that blurred boundaries between festivity and depravity.

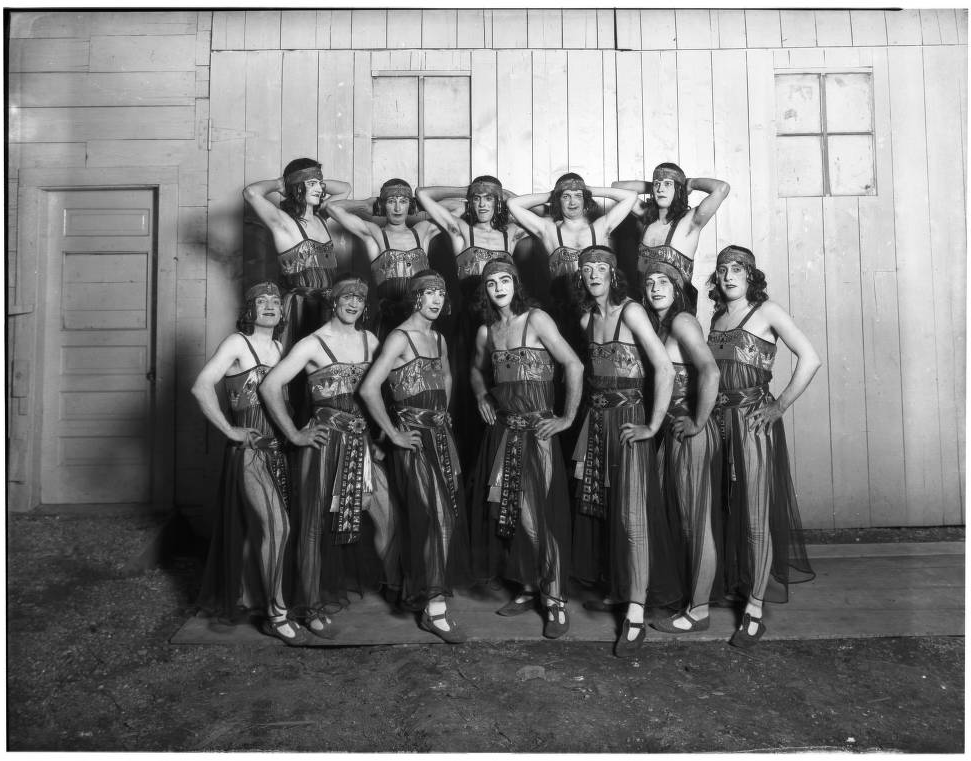

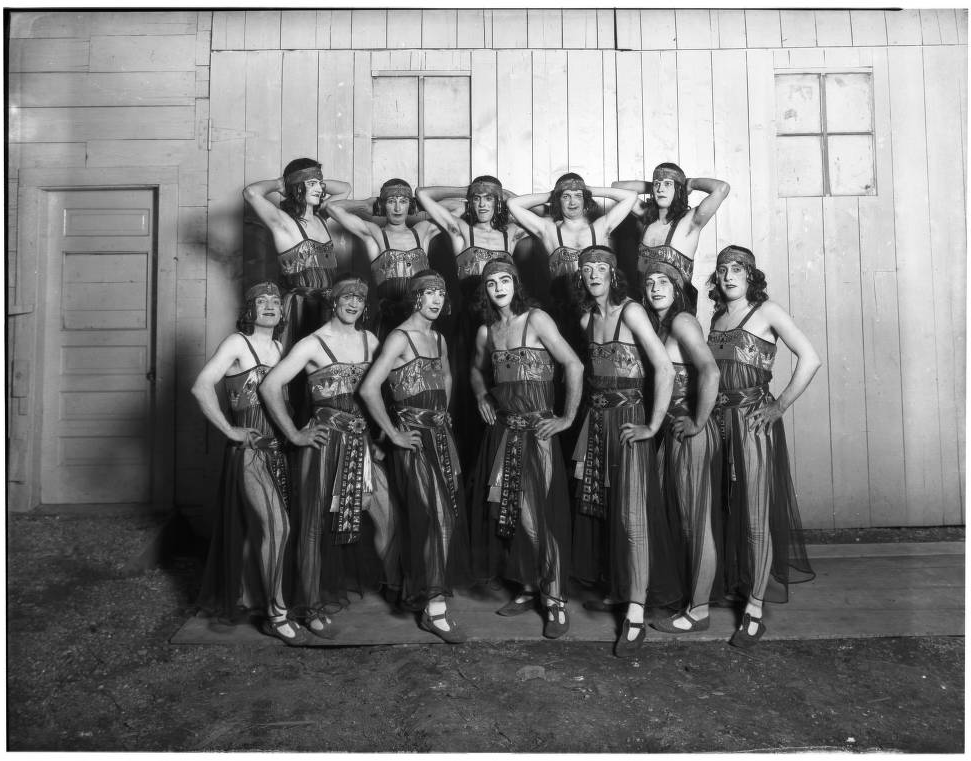

The group's Mardi Gras-styled partying, with elaborate coronations crowning a king and queen of the mythical Kingdom of Quivira, devolved into grotesque spectacles where men and boys paraded in women's clothing or as Egyptian goddesses, injecting innocence into adult revelry. Fantasy themes like "The Roman Hippodrome," "King Arthur's Wild Goats," "Trouble in the Tropics," and "Hi-Jinx in Hades" masked carnivalesque excesses, but the inclusion of boys—dressed in drag and thrust into public displays—hints at a sinister grooming under the guise of tradition. While no exact year marks the start of child involvement in these pageants, historical accounts suggest youths were drafted as early as the organization's formative decades, with the youngest potentially pre-teens, exposed to cross-dressing and mythological role-play that normalized boundary violations among the powerful.

Ak-Sar-Ben's operations thrived on closed membership structures and private ceremonies, enforcing exclusivity that shielded its inner workings from scrutiny. Selective initiation drew from Omaha's business elite, fostering a hierarchy where rituals reinforced dominance and secrecy. These private events, steeped in symbolic pageantry, cultivated networks of influence while limiting external oversight, creating a fertile ground for unchecked behaviors that extended beyond mere celebration.

The organization's horse racing venues, including the Ak-Sar-Ben racetrack established in 1919, generated revenue amid fluctuating gambling regulations, but served as a facade for deeper entanglements. Legalized pari-mutuel wagering in the 1930s bolstered economic claims, yet declining attendance by the 1990s—due to casino competition—mirrored the group's eroding public image. Behind the spectacle, these assets funneled resources into dubious alliances, amplifying the fraternity's grip on regional power.

Ruled by a Board of Governors comprising corporate titans in the late 1980s, Ak-Sar-Ben intertwined with predatory networks, as executives like ConAgra's Charles "Mike" Harper and Union Pacific's Michael H. Walsh poured millions into the Franklin Credit Union. These deposits and contributions supported ![]() , whose scandalous operations alleged child exploitation, revealing how the board's informal and formal arrangements propped up a system of abuse under philanthropic cover.

, whose scandalous operations alleged child exploitation, revealing how the board's informal and formal arrangements propped up a system of abuse under philanthropic cover.

Craig Spence's tangential ties to these circles further darkened Ak-Sar-Ben's legacy, his 1989 scandal of homosexual escorts and blackmail intersecting with Omaha's Republican elite during the Franklin era. Though unconfirmed as a member, Spence's elite machinations amplified suspicions of interstate networks preying on vulnerability, with the Franklin allegations casting a pall over the fraternity's influential roster.

The Union Pacific Railroad's deep connections symbolized Ak-Sar-Ben's economic stranglehold, with executives participating in leadership and events that blurred corporate and civic lines. This nexus extended to the Franklin Community Federal Credit Union, operational from 1970 under King, collapsing in 1988 amid embezzlement—exposing how railroad-backed influence intertwined with exploitative schemes, all under the fraternity's umbrella.

Even as allegations surfaced and were dismissed as hoaxes, Ak-Sar-Ben began dissolving its traditional facade in the early twenty-first century, transitioning assets to charitable foundations like the Aksarben Foundation. Ending coronations in 2018, the group pivoted to scholarships and grants, masking its history of exclusivity with transparent philanthropy—yet the shift coincided with lingering shadows from Franklin, suggesting a calculated retreat from exposure.

In essence, the Knights of Ak-Sar-Ben embodied a malevolent undercurrent in Omaha's elite society, its name a coded emblem of dominion over the young, perpetuated through priest-sanctioned symbolism and child-involved revelry. As the organization faded, its dissolution failed to erase the taint of exploitation, leaving a legacy of power abused in the name of progress.